Dive into the thriving world beneath the deep blue seas, where delicate ancient corals and magnificent aquatic creatures paint a vivid psychedelic canvas of marine life in the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) of Australia, the largest tropical coral system that is about 1,430 miles long. Picture the awe-inspiring sensation of walking on pristine sandy beaches, the sound of sand crackling beneath your feet, with no soul in sight for miles.

As you gaze out towards the azure waters, illuminated by sun rays dancing on the surface, envision an underwater symphony featuring a diverse cast of fish, turtles, and crustaceans. Imagine basking under the shade of a pandanus tree, inhaling the sea salt aroma, and absorbing the truly spectacular sights, sounds, and colors that define the sensational wonder of the GBR.

Yet, this picturesque paradise is tragically susceptible to the onslaught of natural and man-made disasters. Cyclones, global warming, starfish, sediment run-offs, and plastic wastes threaten the very existence of the coral barrier. Let’s delve into the harrowing impact of these calamities on the Great Barrier Reef.

1) Cyclones:

The Great Barrier Reef (GBR) endures the relentless assault of cyclones, mighty storms that unleash havoc upon its delicate coral ecosystems. Disturbing dates and statistics paint a vivid picture of an escalating threat to the resilience of the Great Reef. Research from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) reveals a disconcerting truth – cyclones can wreak havoc up to 1,000km away from their path, extending the reach of their destructive impact.

The Great Barrier Reef (GBR) endures the relentless assault of cyclones, mighty storms that unleash havoc upon its delicate coral ecosystems. Disturbing dates and statistics paint a vivid picture of an escalating threat to the resilience of the Great Reef. Research from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) reveals a disconcerting truth – cyclones can wreak havoc up to 1,000km away from their path, extending the reach of their destructive impact.

Among these cyclonic assailants, several, notably Debbie, Marcia, Yasi, Larry, Orson, and Tracy, ranging from category 3 to 5, have left an indelible mark on the coral sanctuary. TC Yasi, in particular, stands out, causing the most significant loss of coral cover in a 24-hour period since 1985. The aftermath surveys showcase the devastating impact on popular snorkeling spots like Blue Pearl Bay and Manta Ray Bay, leaving coral reefs such as Lunchon Bay, Maureen’s Cove, and Butterfly Bay partly destroyed.

Debbie, a ferocious Category 4 cyclone, recorded maximum wind gusts at 263km/h, leaving roofs lost, properties destroyed, and thousands without power. Marcia, a formidable Category 5 cyclone, battered central Queensland with wind gusts of 208km/h, causing extensive damage. Yasi, a destructive Category 5 in 2011, wreaked havoc in north Queensland with estimated wind gusts of 285km/h. Larry, a menacing Category 4/5 in 2006, left widespread infrastructure damage and disrupted road and rail access.

The Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), and numerous stakeholders tirelessly study the impact of these cyclones and the subsequent recovery phase. Despite the adversity, there is a glimmer of hope as severely impacted reefs exhibit signs of recovery, with coral cover increasing by an average of 4% between 2011 and 2013 at re-surveyed locations.

As the Great Barrier Reef battles against the ferocity of cyclones, the collective efforts of researchers and environmental stewards become paramount in securing the future of this natural wonder.

2) Global Warming:

Rising temperatures, fueled by global warming, cast a looming shadow over the Great Barrier Reef, threatening its vibrant colors and underwater spectacle. The urgency for global climate action to protect this natural wonder cannot be overstated.

Rising temperatures, fueled by global warming, cast a looming shadow over the Great Barrier Reef, threatening its vibrant colors and underwater spectacle. The urgency for global climate action to protect this natural wonder cannot be overstated.

As temperatures soar, the repercussions on the Great Barrier Reef are profound. Coral bleaching, a distressing consequence of elevated temperatures, endangers the kaleidoscopic hues that define this marine marvel. Alarming facts and figures underscore the imperative need for immediate climate action to shield the Great Barrier Reef from the devastating impacts of global warming.

A unique study on Pacific green sea turtles amplifies the alarming repercussions of climate change. Researchers, seeking to discern the gender ratio of these creatures, conducted a daring “turtle rodeo.” Launching themselves like bull wrestlers onto swimming turtles, they gently guided the creatures to shore, examining their DNA, blood samples, and gonads. The findings were staggering – the largest green sea turtle rookery in the Pacific Ocean now witnesses a drastic imbalance, with female turtles outnumbering males by at least 116 to 1.

The sex of sea turtles is intricately linked to the incubation temperature of their eggs, making them vulnerable to climate-induced shifts. With rising global temperatures favoring female offspring, the imbalance poses a significant threat to the persistence of sea turtle populations.

The implications are clear: climate change jeopardizes the delicate balance of life in the Great Barrier Reef. As air and sea temperatures continue to rise, urgent and concerted efforts are essential to secure the future of this marine masterpiece. The call to action is now, as we navigate a changing climate impacting the very essence of the Great Barrier Reef.

The Great Barrier Reef (GBR) also faces a multi-faceted assault from rising temperatures driven by global warming. Beyond coral bleaching, various dimensions of this climate crisis threaten the very essence of this underwater wonder.

A) Ocean Acidification: Elevated CO2 levels, a consequence of global warming, lead to ocean acidification. This disrupts the delicate balance of the Great Barrier Reef’s ecosystem, hindering the ability of corals to build their calcium carbonate skeletons. The structural integrity of coral colonies becomes compromised, impacting the overall health of the reef.

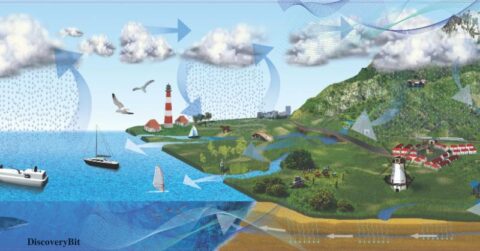

B) Sea Level Rise: With the global rise in temperatures, polar ice caps melt, contributing to an increase in sea levels. While sea level rise itself may not directly impact water temperatures, the warming of the oceans poses a significant threat to the Great Barrier Reef. Elevated sea surface temperatures can disrupt the symbiotic relationship between corals and their algae, a critical factor for the reef’s survival. Additionally, higher sea levels may jeopardize photosynthesis in coral reefs, as increased water depth reduces the amount of sunlight reaching the corals and their symbiotic algae, further challenging the delicate balance crucial for their health.

C) Extreme Weather Events: Global warming intensifies extreme weather events, exposing the Great Barrier Reef to more frequent and severe cyclones. These storms can cause physical damage to coral structures, exacerbating the challenges posed by coral bleaching. The cumulative impact of these events can hinder the reef’s recovery and resilience.

D) Altered Ocean Circulation: Changes in global temperatures influence ocean currents, altering the circulation patterns around the Great Barrier Reef. This can lead to shifts in nutrient distribution, affecting the availability of essential nutrients for coral growth and disrupting the delicate balance of the marine ecosystem.

E) Shifts in Marine Life Behavior: The warming of ocean waters prompts shifts in the behavior and distribution of marine life around the Great Barrier Reef. This can impact the availability of food sources for coral and create imbalances in the ecosystem, further challenging the reef’s ability to adapt and thrive.

The urgency for global climate action is undeniable. The multifaceted impacts of global warming on the Great Barrier Reef underscore the need for concerted efforts to mitigate climate change and preserve this natural wonder for future generations. As we navigate these troubled waters, safeguarding the Great Barrier Reef requires a collective commitment to sustainable practices and environmental stewardship.

3) Plastic Wastes:

Tons of plastic waste infiltrate this Great Barrier Reef (GBR), imperiling marine life and upsetting the delicate balance beneath the waves.

Tons of plastic waste infiltrate this Great Barrier Reef (GBR), imperiling marine life and upsetting the delicate balance beneath the waves.

Plastic items emerge as a formidable threat to the GBR, with an estimated 11.1 billion plastic items entangled on coral reefs across the Asia-Pacific region. Shockingly, this number is projected to surge by 40% by 2025. Effective plastic waste management becomes critical in curbing diseases that jeopardize both ecosystem health and human livelihoods.

A groundbreaking study underscores the devastating impact of plastic on coral reefs. Examining 124,000 reef-building corals from 159 reefs in the Asia-Pacific region, researchers found that the likelihood of a coral reef experiencing diseases skyrockets to 89% upon contact with plastic. In stark contrast, coral reefs untouched by plastic face a mere 4% possibility of disease.

The complexity of corals plays a pivotal role, with more intricate corals being eight times more susceptible to the ravages of plastic, especially the spiky coral reefs. These corals are prone to entanglement, and the likelihood of disease increases twentyfold. Plastic induces light deprivation, releases toxins, and creates an environment conducive to disease development, as highlighted by the research team.

Furthermore, plastic doesn’t discriminate; it disproportionately affects microhabitats for reef-associated organisms. Plastic promotes microbial colonization by pathogens, triggering disease outbreaks in the ocean. The staggering levels of plastic in the oceans reflect a dire mismanagement of plastic wastes entering the waters, signaling an urgent need for comprehensive solutions to protect the invaluable Great Barrier Reef. The time to act against the plastic peril is now, ensuring a sustainable future for this ecological wonder.

Additional ways through which plastic can impact the Great Barrier Reef (GBR):

a) Physical Damage to Coral Structures: Large plastic debris, including bags and fishing gear, can physically damage coral structures. This direct contact can break or smother coral, inhibiting growth and contributing to habitat degradation.

b) Chemical Contamination: Plastic debris often contains harmful chemicals, including additives and pollutants absorbed from the surrounding environment. When plastics break down, these chemicals can leach into the water, negatively impacting the water quality around the GBR and affecting the health of marine life.

c) Microplastic Ingestion: Microplastics, tiny particles resulting from the breakdown of larger plastic items, are ingested by various marine organisms. When these organisms, such as small fish and invertebrates, are part of the GBR food chain, the introduction of microplastics poses a threat to the entire ecosystem.

d) Altered Light Conditions: Floating plastic debris on the water’s surface can alter light penetration into the ocean. This affects the photosynthetic activity of symbiotic algae living within coral tissues, disrupting the crucial relationship between corals and their symbionts.

e) Transport of Invasive Species: Plastic debris can act as a raft, transporting invasive species to new locations. These species may outcompete native organisms and disrupt the ecological balance of the GBR, potentially leading to the introduction of harmful pathogens.

f) Entanglement of Marine Life: Larger plastic items, such as abandoned fishing nets and lines, pose a risk of entanglement for marine life. This can lead to injury or even death for animals like turtles, fish, and other species that inhabit or migrate through the GBR.

g) Sedimentation Impact: Plastics on the seafloor can trap sediments, altering natural sedimentation processes. This can affect the settlement and recruitment of coral larvae and other marine organisms, influencing the overall health of the reef.

Addressing the multifaceted impact of plastic pollution on the GBR requires comprehensive conservation measures, waste management strategies, and global initiatives to reduce plastic consumption and enhance ocean health.

Starfish Outbreaks:

Starfish outbreaks, particularly the predatory Crown-of-Thorns Starfish (COTS), pose a significant threat to the Great Barrier Reef. COTS feed on coral tissues, causing extensive damage and contributing to coral loss. Outbreaks, often exacerbated by nutrient runoff, can lead to widespread coral destruction, impacting the reef’s biodiversity and resilience.

Large-scale coral depletion weakens the ecosystem’s ability to recover from other stressors like bleaching and disease. Effective management strategies, such as targeted culling and addressing underlying causes like water quality, are essential to control starfish outbreaks and mitigate their detrimental effects on the Great Barrier Reef’s ecological balance.

The battle against the starfish menace unfolds beneath the crystal-clear waters of the Great Barrier Reef, where the fate of the world’s largest coral reef system hangs in the balance. Join the exploration of this ecological threat and the race to preserve the natural wonder that is the Great Barrier Reef, Australia’s crown jewel.

Sediment Run-offs:

Sediment run-offs, primarily from land clearing and construction, severely impact the Great Barrier Reef. Excessive sedimentation clouds the water, reducing light penetration vital for coral photosynthesis.

This process, known as turbidity, harms coral growth and lowers their resilience to stressors like climate change. Sedimentation smothers corals, affecting their feeding and reproduction. Additionally, it disrupts the recruitment of new corals and contributes to the spread of coral diseases.

The overall result is a degradation of the reef’s health and loss of biodiversity. Implementing erosion control measures and sustainable land practices is crucial to mitigating the detrimental effects of sediment run-offs.

Chemical Run-offs:

Chemical run-offs, primarily from agricultural activities and urban areas, pose grave threats to the Great Barrier Reef. Pesticides, fertilizers, and pollutants carried by runoff water harm coral health and hinder reproduction.

These chemicals contribute to coral bleaching, weakening the resilience of the reef to climate change stressors. Nutrient enrichment fuels harmful algal blooms, smothering coral and disrupting the delicate balance of the ecosystem. The decline in water quality adversely affects marine life, leading to the loss of biodiversity. Mitigating chemical run-offs through improved land management and conservation efforts is imperative to safeguard the Great Barrier Reef’s vitality.

Overfishing:

Overfishing poses severe threats to the Great Barrier Reef, jeopardizing its delicate ecosystem. Excessive fishing depletes key species, disrupting the balance and diversity of marine life. The removal of apex predators can trigger cascading effects, leading to an overpopulation of certain species and a decline in others.

Overfishing poses severe threats to the Great Barrier Reef, jeopardizing its delicate ecosystem. Excessive fishing depletes key species, disrupting the balance and diversity of marine life. The removal of apex predators can trigger cascading effects, leading to an overpopulation of certain species and a decline in others.

This imbalance can impact coral health, as some fish play crucial roles in cleaning and maintaining reef ecosystems. Furthermore, overfishing contributes to habitat degradation and coral vulnerability, intensifying the reef’s susceptibility to climate change impacts. Sustainable fishing practices are crucial to preserving the Great Barrier Reef’s ecological integrity and biodiversity.

The Great Barrier Reef, a national treasure, hangs in the balance. Join the mission to preserve this ecological marvel, as we navigate through the turbulent waters threatening its existence.

Australia’s Bold Plan to Safeguard the Great Barrier Reef:

Australia has taken a monumental step to protect the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), forever banning the disposal of port-related capital dredge material in the entire World Heritage Area. This federal ban, announced at the World Parks Congress in November 2014 and enacted into law on June 2, 2015, reflects a resolute commitment to preserving this ecological wonder.

Australia has taken a monumental step to protect the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), forever banning the disposal of port-related capital dredge material in the entire World Heritage Area. This federal ban, announced at the World Parks Congress in November 2014 and enacted into law on June 2, 2015, reflects a resolute commitment to preserving this ecological wonder.

Over the past 18 months, the number of capital dredging proposals placing dredge material in the marine park has dwindled from five to zero. Capital dredging for ports is now restricted to established priority ports—Gladstone, Hay Point/Mackay, Abbott Point, and Townsville—within legislated port limits, showcasing a strategic approach to balance development and conservation.

The Reef 2050 Plan, introduced to strengthen Australia’s reef management, engages all levels of government, the community, traditional owners, industry, and the scientific community. This collaborative effort aims to improve, enhance, and maintain the Reef’s health while delivering ecologically sustainable development.

Based on the best available scientific research and insights from 40 years of cooperative management, the Reef 2050 Plan sets concrete targets and actions. Both the Australian and Queensland governments are dedicated to achieving optimal outcomes for the future protection and management of the Reef.

Constant communication and education are pivotal to the success of reef protection. The urgency to address challenges requires overcoming “news fatigue” and actively engaging with the government. As the upcoming general election approaches, it serves as a crucial opportunity to initiate a dialogue and advocate for the critical issues facing the Great Barrier Reef.

Australia’s commitment to the Reef 2050 Plan demonstrates a bold stance in the face of environmental threats, setting an example for global conservation efforts. The Great Barrier Reef stands as a testament to the power of collaborative action in safeguarding our planet’s natural wonders.

Additional major ways to protect the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) that complement the strategies mentioned earlier:

a) Enhanced Water Quality Management: Implementing strict regulations and practices to minimize agricultural runoff and sedimentation, reducing the impact on water quality around the reef. This includes adopting sustainable farming practices and efficient nutrient management.

b) Invasive Species Control: Developing and implementing programs to control and manage invasive species that may threaten the balance of the GBR ecosystem. Preventing the introduction of non-native species is crucial for maintaining biodiversity.

c) Climate Change Mitigation: Implementing measures to address climate change, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This can involve supporting renewable energy initiatives, promoting energy efficiency, and actively participating in global climate agreements.

d) Community Engagement and Education: Fostering awareness and understanding of the GBR’s significance among local communities, tourists, and stakeholders. Education programs can empower individuals to make sustainable choices and actively contribute to reef conservation.

e) Scientific Research and Monitoring: Continuously investing in scientific research to better understand the GBR’s ecosystems, monitor changes, and identify emerging threats. Regular assessments help guide conservation efforts and adapt strategies to evolving challenges.

f) Sustainable Tourism Practices: Implementing guidelines and regulations for the tourism industry to ensure that activities are sustainable and minimize environmental impact. This includes promoting responsible snorkeling, diving, and boating practices.

g) Coral Restoration Initiatives: Supporting coral restoration projects that involve coral propagation, transplantation, and other methods to enhance coral recovery. These initiatives can play a vital role in restoring damaged reef areas.

h) International Collaboration: Engaging in collaborative efforts with neighboring countries, international organizations, and the global community to address transboundary issues, share knowledge, and coordinate conservation strategies on a broader scale.

i) Research and Development of Alternative Materials: Investing in research to develop and promote alternatives to plastic materials, reducing the amount of plastic waste entering the GBR. This includes exploring biodegradable materials and sustainable packaging solutions.

j) Legislative Measures and Enforcement: Strengthening and enforcing legislation related to marine conservation and reef protection. This involves penalties for illegal activities, strict adherence to fishing quotas, and proactive measures to prevent overfishing.

These comprehensive approaches, combined with the existing strategies, form a holistic framework for safeguarding the Great Barrier Reef and ensuring its resilience for future generations

Reference

Tags: Australia barrier reef conservation coral barrier Ecosystem Great Barrier Reef great barrier reef australia Nature Ocean plastic wastes Pollution the great reef Water conservation